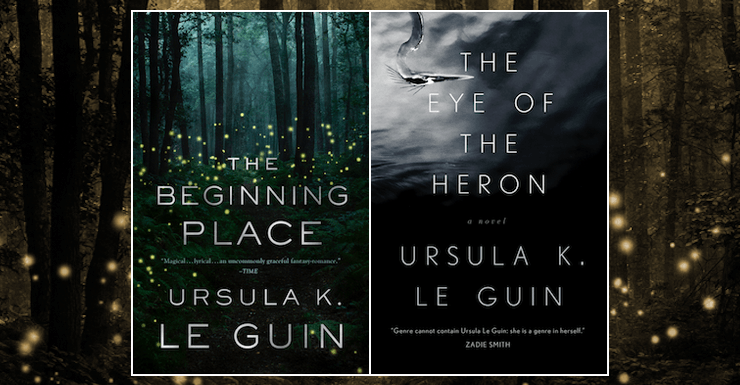

The Beginning Place and The Eye of the Heron are among the first of Ursula K. Le Guin novels to be re-released since her death in January 2018. They’re also two of her lesser-known works; published in 1980 and 1978 respectively, and each clocking in at around 200 pages, it’s not surprising that they’d be so easily lost in an oeuvre of 22 novels and countless shorter pieces, including seminal pieces like The Dispossessed and “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas.” The novels are “lesser” in other ways as well, which is not a thing that pleases me to say, since this is also the first review of her work that I’ve written since January.

Jonathan Lethem once said of Le Guin that she “can lift fiction to the level of poetry and compress it to the density of allegory.” And this is true of all her works, regardless of their greater or lesser qualities. The closer they lean into their allegorical structures, though, the more didactic they become, the less pleasure their poetry elicits. The Beginning Place—about two lost modern souls finding love in a pre-modern alternate universe—and The Eye of the Heron—about a nonviolent revolt on a former prison colony—are firmly in the category of allegory. They wear their themes on their sleeves; their characters are mouthpieces for ideas. But in spite of all that, the novels are still Le Guin, still full to burst with hope and truth—not just socio-political, but emotional. It’s a testament as much to Le Guin’s character and ethic as it is to her writing that these morality tales are still, well, not bad.

Buy the Book

The Beginning Place

The Beginning Place tells the now familiar tale of an unremarkable man accidentally stepping into a new world, only to find a sense of purpose when its inhabitants become convinced that he’s a hero. As with so many of this tale’s variants, (The Lego Movie, Ender’s Game, Wanted), this man, Hugh, is second to arrive, after a more competent female counterpart, Irene, who is not greeted as a hero but who is forced nonetheless to help him in his quest. The novel is less critical of this gendered trope than I’d have liked, but a generous reading would say that’s because its actual project lies elsewhere. Both Hugh and Irene have become disillusioned with the modern world, not just due to its cityscapes and dead-end jobs, but because they are trapped in generational and gendered narratives wrought by their parents. The Beginning Place is less a novel about finding ourselves in a magical new world, as much as it is about trying to create a life, a relationship, a worldview different from the ones you’ve inherited. I found myself at its midpoint bemoaning its compulsory heterosexuality, but by its end appreciating the graceful ways it attempted to deal with the perennial literary themes of generational trauma and self-actualization.

The Eye of the Heron is on the more political end of the socio-political allegory. In this novel, the former prison colony of Victoria is divided into city-dwellers (“bosses”) and the working townsfolk (Shantih). The Shantih arrived as non-violent political prisoners, ideological and peaceful even in the face of starvation and forced labor. The bosses, though, are a more power-hungry, unethical class of criminal, and when the Shantih arrive, they begin to re-make Victoria in Earth’s image: hierarchical, cruel, and gendered. Heron is the story of Lev, a young rebel Shantih, and Luz, the daughter of a boss. Initially published on the tenth anniversary of Martin Luther King’s death (this year marks the fiftieth), its entire thesis is rooted in the success of nonviolent philosophy. Not a terrible message—and I won’t lie, I’m a sucker for books about political rebellion—but having read The Dispossessed, this novel feels like a less-developed and rather toothless knock-off. Absent are the complex conversations about oppression and revolution that existed in historical nonviolent movements, and absent are any explicit acknowledgements of race and class-based oppression. Instead, Heron is focused on good guys and bad guys, and, to some extent, the inability of a society to start from scratch.

Buy the Book

The Eye of the Heron

The throughline of both novels—and why I think Tor published them concurrently this month—is embodied by a line that is repeated in both of them, wherein a character describes a setting as “a beginning place.” In both books, characters struggle against history and inheritance, fighting to create a kinder and more gentle reality. And yet, while Le Guin at times wrote of easy answers, she never wrote of easy paths to realizing them. The Beginning Place and The Eye of the Heron contain utopias of sorts, promised lands that are utterly divorced from the pain and injustices of reality; but the characters never truly reach them, at least within the confines of their stories. They are forced to recon with the past, even as they create something new.

It is hard for me to say I liked or disliked these novels, and not just because I, like so many other readers, am still mourning the loss of a hero and an architect of hope. Even Le Guin’s worst books move me, and in recent years, they have been a necessary antidote to the cynicism that inevitably creeps into criticism and dissent. The Beginning Place and The Eye of the Heron are not great, and I’d never recommend them to a first-time reader—but to those that miss Le Guin’s prose, and who want above all to be moved to a kind of hope in the dark, I’d recommend them.

The Beginning Place is available from Tor Teen; The Eye of the Heron is available from Starscape.

Em Nordling reads, writes, and manages research in Louisville, KY.